Just north of Lochsa Lodge in the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest sits a stretch of wilderness as unique as the history that shaped it: the Great Burn. A landscape marked by ash, regrowth, history, and a conservation legacy and future, the Great Burn is a region that takes its name from a catastrophic 1910 wildfire that consumed three million acres across Montana and Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains, claiming 87 lives and forever changing forest management practices in the American West.

The Great Burn region is roughly 250,000 acres of recommended wilderness situated along the Idaho-Montana border. Fire and time have shaped this region into a place of extremes: alpine lakes fill the valleys of rocky basins, ancient cedar groves grow in its ravines, and breathtaking ridgeline views go on for miles. It also encompasses the largest unprotected roadless area in the region—one of the last truly wild places.

For visitors staying at the Lodge, the Great Burn offers both a window into the past and a chance to experience some of the wildest country left in the Lower 48.

This is the story of how one devastating fire created a conservation legacy, why protecting this area matters more than ever, and how you can experience the Great Burn and all of its majestic beauty for yourself.

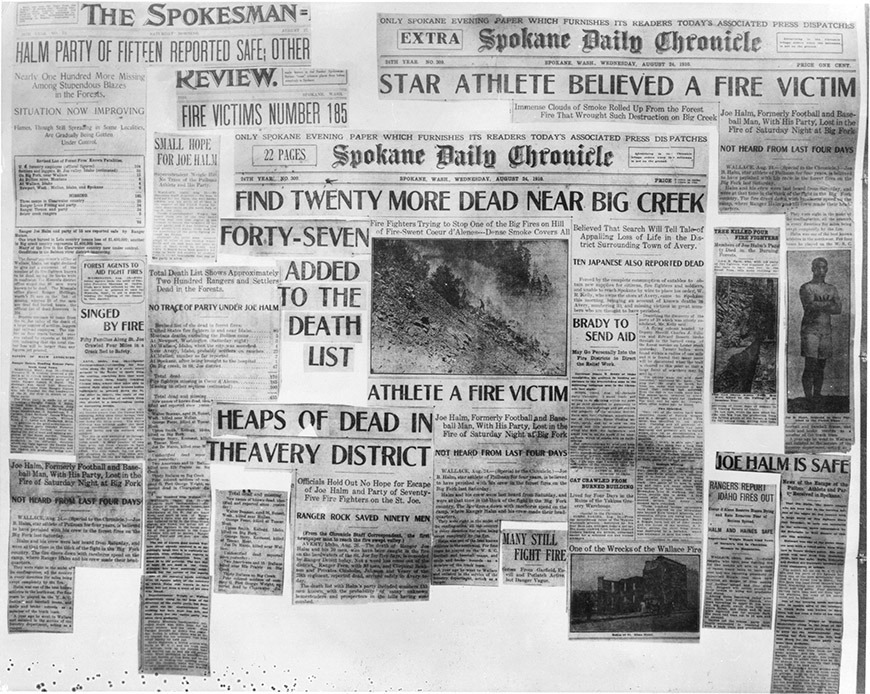

The Historic Fires of 1910

The summer of 1910 started in a way that will feel familiar to those who watch snowpack and precipitation levels every spring ahead of an approaching fire season: the Rockies experienced an ominous spring with rapid snow melt and no rain for months. The forests were tinder-dry, and by June, lightning and human activities had ignited hundreds of small fires across Idaho, Montana, and Washington. The brand-new U.S. Forest Service spent that summer—only the fifth since its founding—scrambling to recruit firefighters, and by mid-August, an estimated 1,000-3,000 individual fires were burning across the region.

Then came August 20, 1910. Palouse winds began to blow at hurricane force, whipping hundreds of separate blazes into a massive firestorm. The fires moved so fast that survivors said they traveled at the speed of a charging horse. Entire mountainsides ignited in seconds, while the sky turned black at noon. In just two days, three million acres were consumed, claiming 87 lives, 78 of them firefighters.

The Big Blowup, as it came to be known, fundamentally changed how America thought about wildfire. Before 1910, there was debate about whether to fight fires or let them burn as a natural part of the landscape. After 1910, the Forest Service received double its budget from Congress and adopted an aggressive fire suppression policy. By 1935, influenced heavily by survivors of the 1910 fires, the agency implemented the “10 a.m. policy“—every wildfire was to be controlled by 10 a.m. the morning after it was reported. It was a policy born from trauma, and one that would shape forest management for decades to come.

Related: Read the USDA’s “When the Mountains Roared: Stories of the 1910 Fire” for more history

The Great Burn Today

More than a century after the flames, the Great Burn has become something unexpected: a testament to nature’s ability to recover and adapt.

Thousands of standing snags still mark the ridgelines—ghostly reminders of 1910—while other slopes have regrown into dense forest. But subsequent fires over the decades burned back much of the young lodgepole pine before it could reseed, and in those places, something different happened. Grasses and wildflowers took over, creating vast alpine meadows and parklands that now define the Great Burn’s character. Old-growth western red cedar groves still thrive in protected valleys, some untouched by the flames.

The Great Burn is the largest unprotected roadless area in the region and one of the largest in the Lower 48. It stretches from Granite Pass in the south to Hoodoo Pass in the north—about 32 miles in a straight line on the Montana side alone.

For wildlife, the Great Burn serves as a critical crossroads. Elk, mountain goats, wolverines, lynx, and black bears all make their home here or pass through on migration routes. The area is considered prime grizzly recovery habitat and a key corridor linking isolated bear populations.

Wilderness Designation: Protecting the Great Burn for the Future

The U.S. Forest Service has given the Great Burn one of the highest wilderness ratings of any area in the National Forest System and has recommended it for wilderness designation since the 1980s. Yet despite more than 20 legislative proposals over the years, the area remains unprotected. It exists in a kind of limbo—managed as wilderness, but without the legal protections that only Congress can provide.

Today, forest plans for the Lolo and Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forests recommend 275,000 acres for congressional designation as the Great Burn Wilderness. It’s managed as “recommended wilderness”—treated like wilderness on paper, but without the permanent legal protections.

Conservation efforts have been driven by a coalition of groups working across state lines. The Great Burn Conservation Alliance, founded in 1971 by University of Montana students who fell in love with the landscape, has led advocacy, education, and on-the-ground stewardship for decades. They work alongside partners including the U.S. Forest Service, Idaho Fish and Game, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, and other conservation organizations to protect the area through forest planning processes, grassroots organizing, and building support for permanent wilderness designation.

Accessing the Great Burn from Lochsa Lodge

The Great Burn’s Idaho trailheads can be accessed at numerous points along Highway 12, making Lochsa Lodge an ideal basecamp for exploring this wild place. Whether you’re planning a day hike to an alpine lake or a multi-day backpacking trip along the ridgeline, the area offers access for every skill level.

Idaho Trailheads (from Highway 12)

Lost Lakes #13: A 3-mile trail to a series of alpine lakes; watch for moose.

Kelly Creek Trailhead: Remote drainage with Hanson Meadows at 10.5 miles, perfect for overnight camping and fishing.

Goose Creek Trailhead: 6-mile trail to Goose Lake with abundant wildlife viewing opportunities.

Montana Trailheads (from I-90)

Schley Trailhead: Access to Kid Lake (2.5 miles from final gate) and upper Kelly Creek drainage.

Cache Creek Trailhead: 7-mile creek-side trail through old burns with wildflowers and rushing water.

Granite Pass Trailhead: Jump on the Stateline Trail to Pilot Knob and Granite Peak with expansive ridge views.

Clearwater Crossing Trailhead: Popular trailhead 1 hour 15 minutes from Missoula; access to Greenwood Cabins (6.5 miles) and Fish Lake (11 miles).

Hoodoo Pass Trailhead: High-elevation access to the Stateline Trail with Heart Lake (4 miles), Dalton Lakes, and Pearl Lakes.

Heart Lake Trailhead: Most popular trailhead in the Great Burn, accessing the scenic Heart Lake in 3 miles.

Maps and Planning Resources

- Great Burn Recreation Map – Available for purchase at greatburn.org/store

- Idaho Trailhead Information

- Montana Trailhead Information

- Lolo National Forest Visitor Map – Available for purchase on the U.S. Forest Service website

Know Before You Go

Summer and early fall (July through September) offer the most accessible conditions, with trails typically snow-free and alpine wildflowers at their peak. High passes like Hoodoo typically melt out in late June or early July. Spring and early summer can present challenges with snowpack at higher elevations and creek crossings swollen with runoff. Winter offers excellent cross-country skiing and snowshoeing opportunities on plowed forest roads, though backcountry avalanche awareness is essential.

We also recommend that you:

- Check current trail conditions with the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest, Powell District: (208) 942-3113

- Be prepared for limited cell phone service throughout the Great Burn

- Practice Leave No Trace principles—this area remains pristine because visitors help keep it that way

- Store food properly (bear canisters recommended)

- Check fire restrictions before heading out

Whether you’re planning a quick day hike from the lodge or a week-long backpacking adventure, the Great Burn offers some of the most spectacular and unspoiled country in the northern Rockies—right in Lochsa Lodge’s backyard.